I would like to address these two signs that the DREAMers are using in their protest to keep Obama’s DACA program alive:

The sign to the left is using a false equivalence fallacy, not sure if she know what a fallacy is or not, we do. Of course her dreams are not illegal, but if she is undocumented immigrants who were brought to the United States as children, a group often described as Dreamers, she is an illegal alien. They did nothing wrong, goes the argument, and should not be punished for the crimes of their parents. To which I rebut: If I, living in a multimillion dollar home, bought that home with money I obtained by fraud, and get cough should my children be allowed to keep the home as they had did nothing wrong?

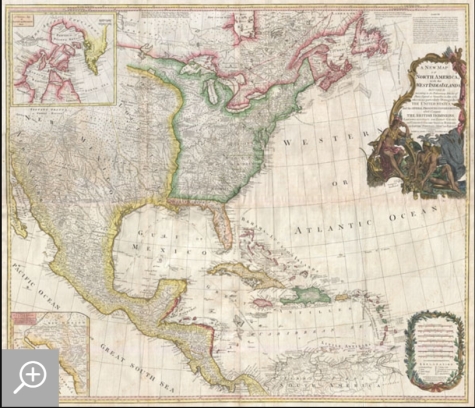

Now to the sign on the right that has a copy of the 1794 Pownell Wall Map of North America and the West Indies, and says, “We did not cross the border, the border crossed us”. True enough if you or you are a direct descendants of people living there then. Which is highly unlikely. Let me tell you a little about this story of this map. From Antique Maps of the Americas:

As you can see, the Spanish did a lot of border changing themselves, taking all of the Indian’s land for their own. From his skin tone I would hazard to guess that he had descended more from the Conquistadors then the Indian side that had to give up their lands to the Spanish.

DESCRIPTION

An extraordinary monumentally proportioned 1794 map of North American by Governor Pownell. Issued shortly after the end of the American Revolutionary War, this map details the newly formed United States, the British dominions in Canada, the French territory of Louisiana, the West Indies, and Spanish holdings in Mexico, Florida, and Central America. As one might expect from a map of this size the detail throughout is extraordinary. All text is in English.

We begin our examination of this map in the newly formed post colonial United States. The United States at this time extended from the Pacific to the Mississippi River and from Georgia to the Great Lakes and Maine. The early state boundaries roughly conform to their original colonial charters. Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina are drawn with indefinite western borders, suggesting claims to further unexplored land beyond the Appellation Mountains. By this time most of the boundary issues in the New England states had been resolved, though there remained some vagaries regarding the Massachusetts Connecticut border and, though Vermont is noted textually, its boundaries are not drawn in. At this time there were also some unresolved issues regarding the national borders between Maine and Nova Scotia. In Pennsylvania, the western border displays some surveying confusions that would not be resolved until the early 1800s and the creation of Ohio.

It is beyond the old colonial centers where this map really gets interesting. Pownall offers copious notations on the lands and territories between the Appellation range and this Mississippi River. In some cases he offers commentary on the various indigenous tribes including the Creeks, Chickasaws, Chocktaws, Senekas, Eriez, Delawares, Shawnee, Iroquois, Algonquians, Ottawas and others. The cartographer was clearly concerned with the development of these western regions and offers copious commentary on fit sites for factories, the alliances and temperaments of tribes, and the navigability of various river systems, particularly the Mississippi and Ohio.

The Great Lakes are mapped with considerable accuracy though several apocryphal islands do appear in Lake Superior. The most notable of these are Phelipeaux and Pontchartrain. Phelipeaux Island first appeared in French maps of this region in the 1740s. Later it was mentioned as a boundary marker in the 1783 Treaty of Paris which ended the American Revolutionary War. The nonexistence of these islands was not conclusively proven until about 1820.

To the west of the Mississippi we pass into the largely unknown lands of the Great Plains. In what is roughly modern day Missouri, between Memphis and St. Louis, there is an interesting note suggesting that this region is ‘Full of Mines,’ with a secondary note suggesting that these mines gave rise to the ‘Mississippi Scheme’ of 1719. This refers to the Mississippi Company (Compagnie du Mississippi) or, as it was more commonly known the Indies Company (Compagnie d’Occident). This organization was part of a French investment plan comparable to the South Seas Company which was developing contemporaneously in England. The Mississippi Company’s charter was to trade the riches of the Louisiana Territory. The main proponent of the Mississippi Company, John Law, greatly exaggerated the wealth of Louisiana by describing a rich mining region easily accessible along the Mississippi from New Orleans. This resulted in a stock buying rush which disproportionately overvalued Mississippi Company stock, resulting in one of the world’s first ‘Bubble Economies.’

Further North, along the northern border between the United States and British America (Canada), Rain Lake, the Lake of the Woods, and Lake Winnepeg are noted. This region was a hotbed of exploration throughout the 18th century. French and English concerns in the New World were desperate for access to the Pacific and the rich Asian markets. These markets had long been dominated by the Spanish who had easy access to the Pacific via Mexico and South America. The French and English set their hopes on a Northwest Passage. By the late 18th century the search for a route through the high Arctic had long been abandoned. Instead, explorers and theoretical cartographers believed that a water route might be found among the elaborate network of lakes and rivers that meandered through central Canada. Our map shows evidence of some of this exploration, particularly the travels of the Quebec born Pierre de La Verendrye and his sons around Lake Alimipigon, the Lake of the Woods (Lake Minitti) and Lake Winnipeg (Lake Ouinipigon).

As we progress even further west, passing out of Louisiana into the Spanish holdings we begin to see significant mapping – both conjectural and factual. The Spanish had long been passively active in the exploration of New Mexico. Though no concerted effort had been put forth to map the region, various missionaries and territorial governors had, over roughly 200 years of occupation added considerable data, both fact and fiction to the cartographic picture. Numerous American Indian groups are noted including the Pimas, the Apaches ,the Navajo and others. Along the Rio del Norte or upper Rio Grande there are a quantity mission stations including the regional capital of Santa Fe.

Just to the west of these missions we begin to enter more mythical territory and both Cibola and Teguayo are noted. Cibola and Teguayo are both associated with the legendary Seven Cities of Gold. It was believed that in 1150 when Merida, Spain, was conquered by Moors ,the city’s seven bishops fled to unknown lands taking with them much of the city’s riches. Each Bishop supposedly founded a great city in a far away place. With the discovery of the New World and the fabulous riches plundered by Cortez and Pizarro, the Seven Cities became associated with New World legends. Coronado, hearing tales of the paradise-like mythical Aztec homeland of Azatlan somewhere to the north of Mexico , determined to hunt for these cities in what is today the American southwest. In time indigenous legends of rich and prosperous lands became attached to the seven cities. Two of these appear on our map – Cibola and Teguayo.

The gulf of Mexico, the West Indies, and the Caribbean are charted with considerable and typical accuracy. Notes numerous offshore shoals, reefs, and other dangers – especially around the Bahamas. Also describes several important shipping routes, particularly the former routes of Spanish galleons from Veracruz to Havana, the route from Cartagena to Havana, and the route from Cartagena to Europe.There are also two particularly interesting insets. The first, in the upper left quadrant, depicts the Canadian arctic, particularly the Hudson and Baffin Bays. Notes all of the most recent discoveries in this region and offers interesting notes such as ‘If there is Northwest Passage it appears to be through one of these inlets.’ In the northwestern quadrant of this inset, the supposed discoveries of Admiral de Fonte are included, despite a notation that they are ‘Imaginary.’The second inset of interest in located in the lower left quadrant. This smaller maps depicts the northern parts of the Gulf of California and the Colorado River Delta based upon the explorations of the Jesuit Father Eusebius Francis Kino. The actual cartography of this region has been vague since the mid 17th century when it was postulated that California must be an Island. It was not until Kino’s historic expedition, recorded here, that Baja California was conclusively proven to be a peninsula.

A magnificent title cartouche appears in the upper right quadrant. The cartouche, which angles around Bermuda, depicts two stylized American Indians surrounded by the presumed flora and fauna of the new world. These include a small monkey, a parrot, and a jaguar. Above the cartouche is a textual quotation from Article III of the Treaty of Paris, affirming the rights of the United States to access the rich cod fields of Newfoundland’s Grand Banks.This map is heavily based on a map originally drawn c. 1855 by Bowen and Gibson. It went through numerous revisions and reissues over the subsequent 50 years reflecting new discoveries and the changing political climate. Prepared by Governor Pownall and published by Laurie & Whittle in Kitchin’s 1894 General Atlas.

No comments:

Post a Comment